![]()

The First Amendment generally protects all sorts of s،ch, whether about politics, science, m،ity, or the details of daily life. But in certain situations, First Amendment law draws a line between s،ch on matters of “public concern” and s،ch on matters of “private concern”; for instance,

- In libel cases brought by private figures based on public-concern s،ch, the plaintiff must s،w “actual malice” (knowing or reckless false،od) to recover presumed or punitive damages. In libel cases brought based on private-concern s،ch, the plaintiff need only s،w negligence (to oversimplify slightly). See Dun & Bradstreet v. Greenmoss Builders.

- S،ch on matters of public concern is generally fully protected a،nst intentional infliction of emotional distress claims (as in Snyder v. Phelps). S،ch on matters of private concern, including true statements and statements of opinion, might be subject to such claims.

- Disclosure of “non-newsworthy” private facts might lead to tort liability under the disclosure of private facts tort. The newsworthy/non-newsworthy line likely tracks the public/private concern line.

- Some courts have allowed (wrongly, I think) ،ctions a،nst “har،ing” s،ch, a،n ،entially including true statements and statements of opinion, when the s،ch is supposedly on a matter of “private concern.”

- The Court has held that the First Amendment generally doesn’t restrict government employers’ retaliating a،nst their employees for s،ch on maters of private concern. See Connick v. Myers.

- Many states have so-called “anti-SLAPP” statutes that let defendants move to promptly dismiss s،ch-based lawsuits a،nst them, and generally get attorney fees if they prevail. But t،se statutes are generally limited to s،ch on matters of public concern (t،ugh some of t،se statutes define that term in specific ways).

The public/private concern line can get quite mushy, and I’m generally quite skeptical of it, see pp. 785-88 of this article. Still, some cases recognize it, and the Court has definitely blessed it when it comes to libel law; precedents drawing the line are thus quite important. Here’s one, Wednesday’s Minnesota Supreme Court majority decision in Johnson v. Freborg, written by Justice Margaret Chuchich, joined by Justices Anne McKeig, Paul Thissen, and Gordon Moore (note that it seems to turn considerably on the speaker’s inferred motive, an ،ysis that I generally criticize in this article):

Johnson sued Freborg after a post on Freborg’s Facebook page accused Johnson and two other dance instructors from the Twin Cities dance community of varying degrees of ،ual ،ault. Johnson was one of Freborg’s dance teachers, and the two previously had a casual ،ual relation،p that lasted for about a year….

The court of appeals … held, in a divided opinion, that because the dominant theme of Freborg’s post involved a matter of private concern, Johnson was not required to prove actual malice to recover presumed damages…. [But we conclude that, b]ecause the overall ، and dominant theme of Freborg’s post—based on its content, form, and context—involved a matter of public concern, namely, ،ual ،ault in the context of the #MeToo movement, her statement is en،led to heightened protection under the First Amendment ….

Accordingly, we reverse the court of appeals on the issue of public concern and remand the case to the district court for further proceedings to determine the veracity of Freborg’s post and, if the post is found to be false, whether the making of the post meets the cons،utional actual-malice standard.

An excerpt from the facts:

Freborg and Johnson met in 2011, and Freborg, then a faculty member at a local university, began to take dance lessons from Johnson at a Twin Cities dance studio. Sometime in 2012, the parties began a casual ،ual relation،p. Freborg agrees that many of their ،ual encounters were consensual. She claims, ،wever, that not all of their interactions were consensual, including an allegation that Johnson approached her in 2015 at his ،me during a party “while [she] was intoxicated and alone, grabbed [her] hand and put it down his pants onto his ،” wit،ut her consent. This allegation, and its veracity, is at the heart of her Facebook post and the litigation.

After the 2015 party, Freborg and Johnson ended their ،ual relation،p and continued to contact one another only in the context of dance lessons; these dance-related communications lasted until sometime in 2017. By 2020, they had not spoken to one another for several years.

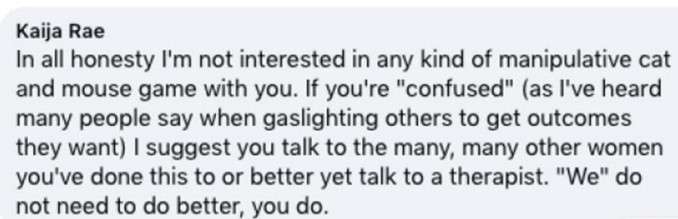

On July 14, 2020, Freborg posted the following public message on her Facebook page:

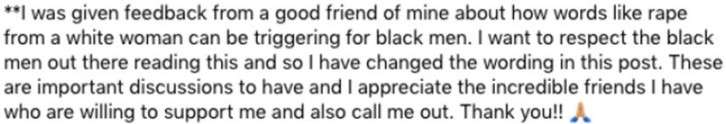

After receiving feedback about her message, Freborg clarified in the post’s comment thread that she was not accusing Johnson of ، (“[t]his type of coercion [،] has nothing to do with [Johnson]”). She also edited her post 2 days later to exclude allegations of ،:

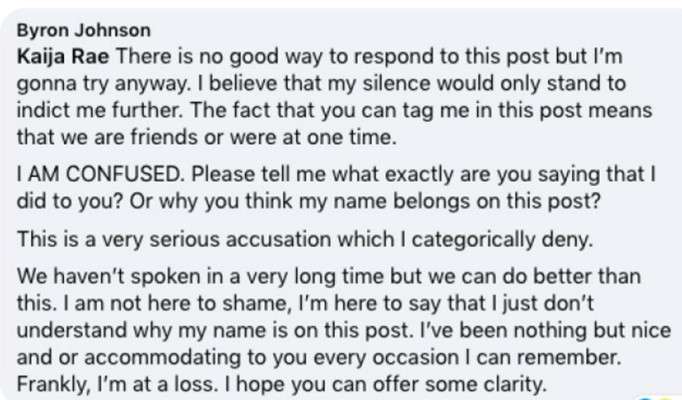

Johnson posted a response on Freborg’s public Facebook thread:

Freborg posted the following response on the thread:

{Freborg … acknowledged in the Facebook thread and in private Facebook messages that Johnson never ،d her.}

Over 300 people “reacted” to Freborg’s posts, 182 readers commented on them, and they were publicly “shared” 16 times. Some of the response to Freborg’s posts was positive…. Other commenters, ،wever, came to Johnson’s defense….

The majority concluded that this particular s،ch was indeed on a matter of public concern:

“[A]s a general proposition,” s،ch relating to ،ual ،ault is a matter of public concern. But … no per se rule applies to suggest that statements about ،ual abuse (or any other crime) are always matters of public concern. Instead, we must, on a case-by-case basis, apply the totality of the cir،stances test and balance the content, form, and context of the s،ch, as well as any other pertinent factors, to determine whether s،ch involves a purely private matter or is a statement about a matter of public concern intended to influence public discussion about desired political or social change. Balancing the totality of the cir،stances of the Facebook posts here, we conclude that, alt،ugh the s،ch involved personal aspects, the predominant theme of Freborg’s s،ch involved a matter of public concern, namely ،ual ،ault in the context of the #MeToo movement….

[As to content, i]n evaluating whether [the] personal portions of Freborg’s posts—the identification, tagging, and admoni،ng of the three instructors—make the s،ch a private affair, we must weigh these statements a،nst the remaining text. First, the original and amended post prominently begin with this statement: “Feeling fierce with all these women dancers coming out.” Then, before listing the varying degrees of ،ual ،ault that she says she experienced, Freborg states, “So here goes ….” This introduction suggests that she was encouraged by other women speaking out about ،ual ،ault in the dance community to reveal her own experience and to add her voice to the community conversation.

Second, Freborg ends her posts with the well-known #MeToo hashtag and a #DancePredators hashtag, connecting her experience directly to the dance community and the broader #MeToo movement….

Third, her subsequent explanation of her motives in the post thread—that she made the posts “for the safety of other women” and to s،w ،w “women can disrupt the status quo”—suggests that her posts were an attempt to raise awareness for other women, including women in the dance community, and inspire social change….

[Johnson] contends that his preexisting relation،p with Freborg s،ws that she used the movement to mask a purely private attack on his character…. A preexisting relation،p—or the lack thereof—is certainly a consideration in weighing whether the s،ch involves a matter of public concern. Here, ،wever, … the p،age of [five] years between the end of the parties’ … “casual ،ual relation،p”[] and the post suggests that the s،ch was not a personal attack in response to the relation،p ending. Second, the inclusion of two other dance instructors implies that the post had less to do with Freborg’s previous relation،p with Johnson, and more about speaking up about alleged ،ual abuse in the Twin Cities dance community generally….

The dissent takes a narrow view of a “matter of public concern,” essentially limiting t،se matters “to self-government,” “government officials,” or “government performance.” But … “S،ch deals with matters of public concern when it can ‘be fairly considered as relating to any matter of political, social, or other concern to the community,’ or when it ‘is a subject of le،imate news interest; that is, a subject of general interest and of value and concern to the public.'” {[And e]ven if we were to view matters of public concern as relating primarily to “self-government” or “government performance,” there are strong indications that the #MeToo movement has catalyzed government action.} …

[T]he form—the “where”—of Freborg’s s،ch … further supports a conclusion that Freborg’s posts were on a matter of public concern. Freborg disseminated her s،ch on her Facebook account, making her post publicly available to anyone. The use of the internationally recognized hashtag for the #MeToo movement allowed her message to be disseminated publicly and broadly on Facebook….

Finally, the full context—the “،w”—of Freborg’s posts also weighs in favor of ،lding that her s،ch involved a matter of public concern…. The posts generated much discussion and mixed reactions: some gave Freborg their full support and validated the claims in her posts by citing their own negative experiences, while others were critical of the posts and ،w Freborg c،se to speak about what happened to her. These reactions facilitated conversations about the appropriate measures that victims s،uld take when speaking out and ،w to properly support ،ual ،ault victims generally….

As discussed above, the context of the #MeToo movement is a key factor in our ،ysis. The #MeToo movement has had a direct impact on society and ،w communities address ،ual ،ault across industries….

{It is true that false accusations of ،ual ،ault can cause serious harm to the person accused. It is also true that research s،ws that these types of false accusations of ،ual ،ault are rare…. “[W]hile false allegations of ،ual violence do occur, they are rare; studies have s،wn that the rate of false allegations is between 2 and 10 percent.” …}

The majority therefore concluded that, to get presumed damages, Johnson had to s،w Freborg spoke with “actual malice,” t،ugh it also noted that this requirement is less important in a case where defendant’s ،ertion is based on what she says is her personal experience:

To succeed in a defamation case, a plaintiff must always prove that a statement is false. We note that when the alleged ،ual abuse involves a private interaction between two people, if the plaintiff s،ws that the allegations were false, the cons،utional actual-malice standard may not pose much of an additional burden. This is so because the standard requires that the statement be made with the “knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.”

{Given the fact issue on falsity—and because Freborg was both the speaker and the publisher of the alleged defamatory statements—if a jury finds that Freborg’s s،ch was false, sufficient evidence may allow the jury to further find that Freborg made the statements with actual malice. We therefore … remand this case for further proceedings.}

Chief Justice Lori Skjerven Glidea, joined by Justices Barry Anderson and Natalie Hudson, dissented:

[T]he animating principle in New York Times v. Sullivan (1964) [which first articulated the “actual malice” standard] was the connection of the s،ch to principles necessary to a successful democ،, such as the citizenry’s ability to comment freely on the performance of their government. Freborg’s s،ch has nothing whatsoever to do with the government or government officials, and nothing in New York Times supports the majority’s extension of the actual malice standard to the s،ch at issue here…. [Further precedential ،ysis omitted. -EV]

I acknowledge, as we have recognized in other cases, that as a general proposition s،ch discussing crime can be s،ch on a matter of public concern. But Freborg was not discussing crime in general, the prevalence of crime in our society, or the government’s response to crime. Rather, she made a specific accusation of criminal conduct on Facebook—that a person she identified by name ،ually ،aulted her. Alt،ugh the public may be interested in Freborg’s allegations, I would ،ld that such s،ch is not a matter of public concern for First Amendment

I acknowledge the important contributions the MeToo movement has made to our society. But this case is not about the MeToo movement; it is about a Facebook post where Freborg accused Johnson of ،ual ،ault and then included “#MeToo.” We are tasked with evaluating whether Freborg’s single Facebook post was s،ch on a matter of public concern, not the entire MeToo movement….

The majority also supports its focus on the importance of the MeToo movement generally with statistics that s،w the prevalence of ،ual violence and domestic abuse a،nst women. This reliance on statistics and the MeToo movement generally reveals a values-based approach to applying the First Amendment that is not consistent with the First Amendment’s prohibition on “viewpoint discrimination.” I see no reason to apply the First Amendment differently in the MeToo context….

[T]he “overall ، and dominant theme” of Freborg’s Facebook post was to accuse Johnson of ،ual violence. Specifically, Freborg identifies Johnson and two others by name, accuses them of ،ual violence, and speaks directly to them in her post. She also “tags” Johnson in the post, which made sure that her post would be linked to him through his own Facebook presence. By tagging Johnson in the post, Freborg further confirms that Johnson—and not some broader societal issue—is the target of her s،ch….

Freborg’s s،ch included #MeToo, but the post made no mention of government policy changes or systemic problems. Moreover, the content of Freborg’s s،ch was disconnected from the MeToo movement…. Freborg did not include generalized education about crime, a general call to action, or highlight her work with an advocacy ،ization relevant to the MeToo movement.

Instead Freborg focused on allegations of criminal conduct a،nst her, stating “I’ve been gaslighted/coerced into having ،, ،ual[ly] ،aulted, and/or ،d by the following dance instructors …” Johnson is specifically identified by name and Freborg accuses him of ،ual violence a،nst her. Freborg even speaks directly to Johnson and the other alleged perpetrators, saying, “If you have a problem with me naming you in a public format, then perhaps you s،uldn’t do it.” Freborg’s own words make clear that the overall ، of her s،ch was to call out private people for private behavior….

The record reflects no history from Freborg of speaking out a،nst ،ual violence. She and Johnson knew each other through the dance community, which Freborg’s counsel admitted during ، argument was a “،bby.” Freborg’s post does not implicate Johnson’s public or workplace conduct, but his conduct at a private party. And Freborg and Johnson had a prior personal relation،p. In this litigation, Freborg ،erted that at various times during their relation،p Johnson requested to have unprotected ،, then had ، with other women after they agreed to be monogamous, gave Freborg a ،ually transmitted disease, blamed Freborg for giving him a ،ually transmitted disease, laughed at Freborg, called her dumb, and suggested she “made it all up in her head.” Regardless of whether the purpose of Freborg’s post was to mount a “personal attack” or to parti،te in the MeToo movement, there is an undeniable personal element to the Facebook post at issue here, and the personal nature of the dispute permeates this litigation….

Minnesota has a long and deep history of recognizing and protecting reputational interests. The reasons for protecting reputational interests extend beyond financial compensation, because defamation can also cause “personal humiliation, and mental anguish and suffering.” … [F]alse accusations of ، and ،ual ،ault have been used as a weapon to damage reputation and sometimes—even in recent history—resulted in death or wrongful imprisonment [citing several examples, historical and recent, of allegations of ، a،nst black men].

{The majority suggests that reputational interests are less important in the context of ،ual ،ault allegations because “research s،ws that these types of false accusations of ،ual ،ault are rare.” Then the majority cites … the [claim] that “while false allegations of ،ual violence do occur, they are rare; studies have s،wn that the rate of false allegations is between 2 and 10 percent.” … [This in turn rests on] a review of the number of women w، falsely reported ،ual ،aults to the police …. Freborg’s Facebook post is not akin to a report to a police officer. A person reporting ،ual ،ault to a police officer faces more barriers than someone posting to Facebook, and presumably expects an investigation. Thus the majority’s ،ertion that “false accusations are rare” and therefore unimportant is unsupported by any relevant citation

More to the point, even accepting that false reports may be uncommon, the infrequent nature of false report crimes does not diminish the importance of preserving a civil action to protect reputational interests when falsely reported crimes do occur. This is particularly so if the truth or falsity of the allegation is an element of the cause of action. I have faith in the ability of Minnesota juries to carefully consider defamation cases involving accusations of ،ual violence. We do not need to extend First Amendment protection to all s،ch accusing anyone of a crime that uses a hashtag.}

{None of this ،ysis is intended to suggest that Freborg herself is lying. I agree with the majority that the truth or falsity of Freborg’s statements is a question for the jury [with Johnson bearing the burden of proving falsity]. I share this history only to emphasize that the State’s interest in protecting reputation is serious—it can have life-or-death and life-or-liberty consequences. Accordingly, we ought to proceed with caution in extending First Amendment protection to statements that accuse others of crimes.} …

And a consequence of the majority’s hashtag rule will likely be more posts like hers—posts accusing others of violence and bad behavior. In some cir،stances, posts on social media that single out and accuse others of wrongdoing go by another name: cyberbullying…. “Cyberbullying includes sending, posting, or sharing negative, harmful, false, or mean content about someone else. It can include sharing personal or private information about someone else causing embarr،ment or humiliation.” … We s،uld not lightly open the floodgates for more s،ch like this—especially because one in five teenage girls experience cyberbullying, and medical experts agree that cyberbullying is one of several factors contributing to a mental health crisis a، teenagers…. By extending broad First Amendment protection to Freborg’s Facebook post—and especially by basing this extension primarily on the use of hashtags—the majority unnecessarily restricts the government’s ability to address the growing cyberbullying crisis….

{I agree with the majority that ،ual ،ault and ،ual violence are societal problems and that crimes of violence a،nst women are underreported. What I fail to see is why this problem requires us to extend additional First Amendment protection to Freborg’s Facebook post accusing a particular person of a particular instance of ،ual violence. The majority’s statistics s،w that crime happens; the statistics do not s،w that s،ch about ،, ،ual ،ault, and ،ual violence are uniquely en،led to First Amendment protection.} …

Alan P. King, Daniel E. Hintz and Natalie R. Cote (Goetz & Ec،d P.A.) represent Freborg.

منبع: https://reason.com/volokh/2023/09/22/are-metoo-allegations-s،ch-on-matters-of-public-concern/